Design is available for sale, benefitting the Seattle Aces.

Author Archives: asexualityarchive

Exploring The Purported Link Between Ejaculation and Prostate Cancer

“Ejaculation prevents prostate cancer!”

So claims the breathlessly excited article that pops up in your news feed. The article talks glowingly about a study that found that the more someone ejaculates, the less likely they are to get prostate cancer. And OBVIOUSLY, the inverse is true, that the less someone ejaculates, the more their prostate rebels against them. “So get to it!”, the article implies, “Start fighting that cancer today!”

That’s the story everyone reads, anyway.

I have seen a number of aces use this as their primary reason for masturbating. In a lot of these cases, the rationale is “I have heard that ejaculation helps prevent prostate cancer, so I masturbate because I have to, not because I want to.” I wanted to explore these studies, see what they’re really saying, and see if there really is a good reason for aces to masturbate in order to prevent prostate cancer.

And what I found…? Well, there’s going to be a lot of numbers and sciencey talk in the post ahead, so if you just want the quick TL;DR, here it is:

If you masturbate solely on the basis that you’ve heard it prevents prostate cancer, you probably shouldn’t waste your time. The studies don’t actually say that it does, the results are a bit mixed, there are a number of significant concerns about the makeup of the study, and even if all of the findings are accurate and true, the true benefit is fairly minimal. I think allowing this myth to stand unchallenged is doing harm to many aces who frequently subject themselves to something they do not inherently want to do based on its advice.

First, a few disclaimers…

I am not a doctor. I have no urology training. For this post, I read the two main papers on the subject, but did not do an exhaustive search of the literature for all the papers on the topic. I freely admit to the possibility that my conclusions here are completely off-base, and will happily correct what I’ve said, should more concrete evidence come to light.

Also, I personally quite like to masturbate. This should in no way be taken as saying that aces shouldn’t masturbate at all. All I want to say here is that the purported reduction in risk of prostate cancer that is supposedly linked to more frequent ejaculations should not be a reason that someone masturbates, particularly if they would not want to masturbate otherwise.

About Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer, as its name implies, is cancer of the prostate. The prostate is a small organ that typically comes as a package deal with a penis and testicles. That means that only about half of the population has a prostate. The other half does not have one, and therefore cannot get prostate cancer. (A similar organ, called the Skene’s Gland is what comes as part of the vagina/clitoris package deal. Skene’s Gland cancer is apparently very rare, much rarer than prostate cancer.) It sits just below the bladder, surrounding the urethra before it heads towards the penis. The ejaculatory ducts coming from the testicles intersect the urethra within the prostate. The prostate’s main purpose is to supply prostate fluid during ejaculation. Prostate fluid helps sperm get around and is a clear to milky white fluid that makes up about 30% of the volume of semen. The prostate is a critical part of the process of ejaculation, hence the interest in a possible link between prostate cancer and ejaculation.

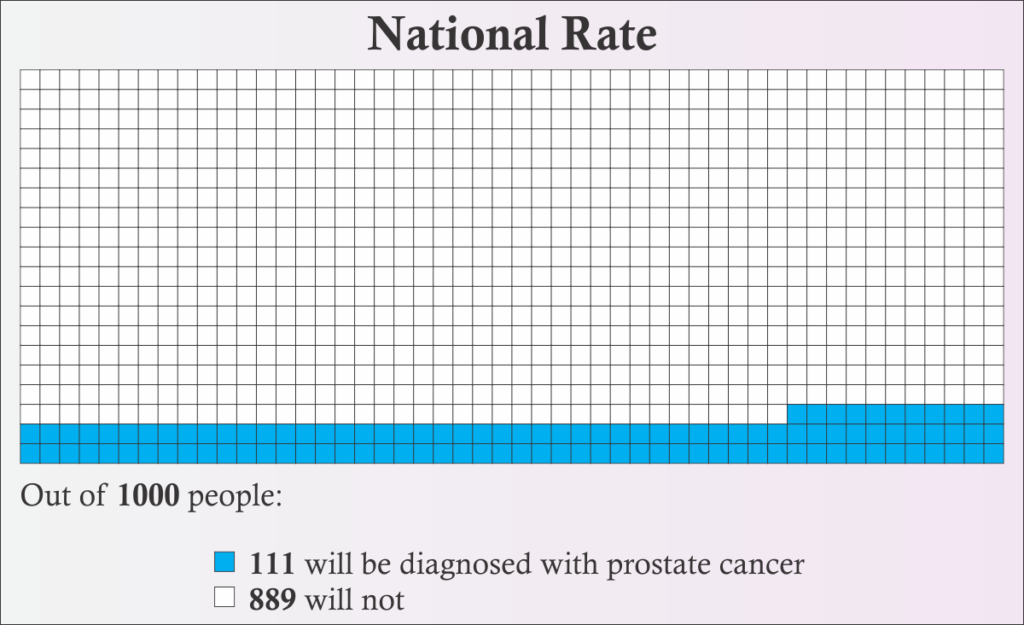

According to the American Cancer Society, about 1 in 9 people with a prostate will eventually be diagnosed with prostate cancer. (Note that this says diagnosed with prostate cancer. Some people who get prostate cancer have no symptoms and will die of other causes without ever being diagnosed.) The majority of those cases are in people over 65 years old. However, only about 1 in 41 will die from prostate cancer. [1]

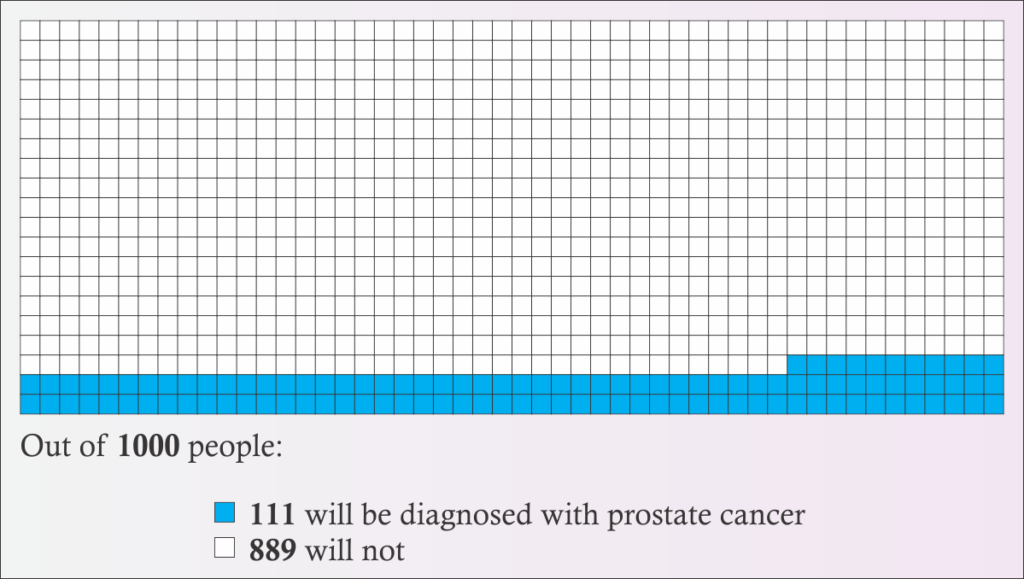

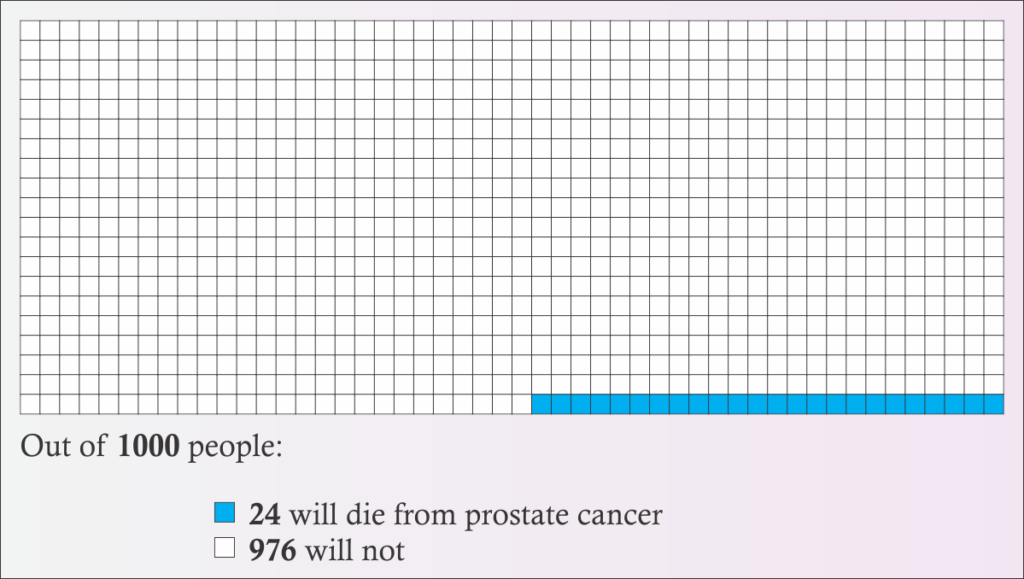

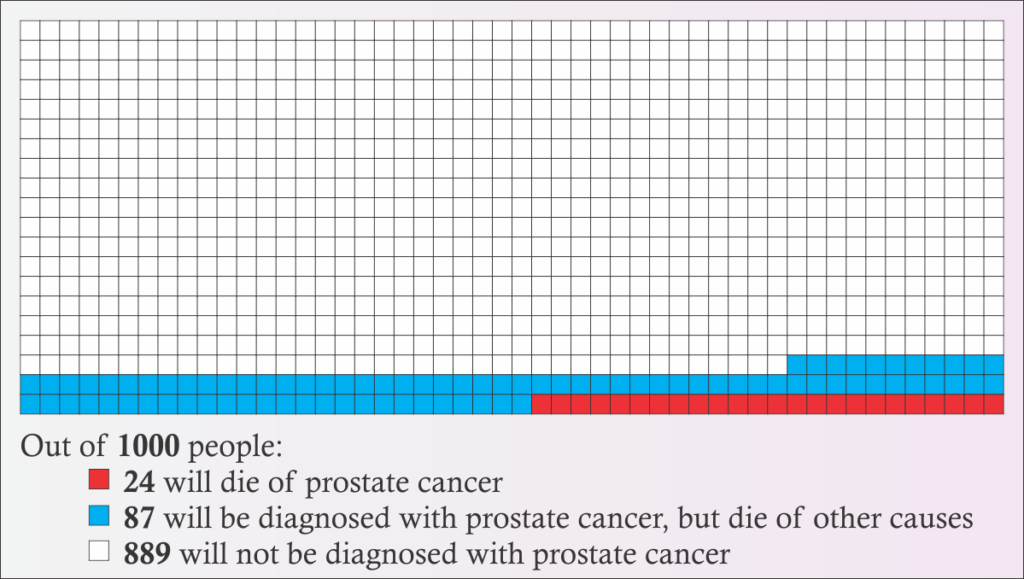

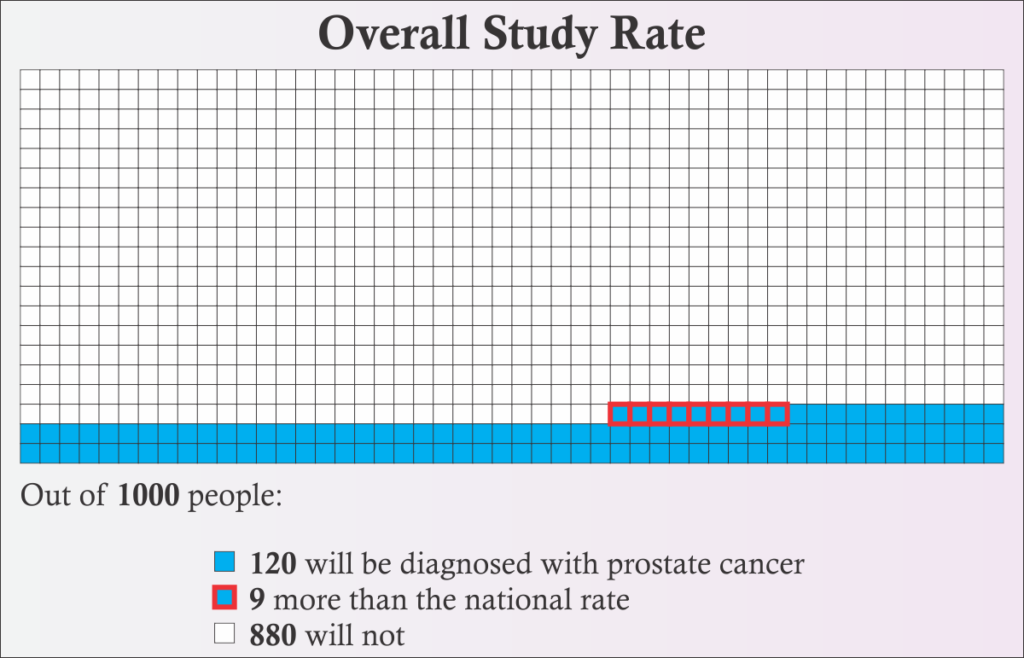

To look at it a different way, if you have a room with 1000 prostate-owning people in it, 111 of them will be diagnosed with prostate cancer within their lifetimes, but 889 will not. [Figure 1] 24 of them will die of prostate cancer, while 976 will not. [Figure 2] And if you combine those two, it means that 87 of the 111 people who are diagnosed with prostate cancer will die of some other cause. [Figure 3] So even if you are diagnosed with prostate cancer, there is an almost 80% chance that something else will be what kills you.

Prostate cancer is one of the most survivable cancers. It has a five year relative survivability rate of 99%. [2] Relative survival is a slightly complicated measure that indicates how likely someone with a disease will survive for a period of time (typically 5 years) compared to the number of similar people who don’t have that disease. A lower number is worse because it means a person is less likely to survive. It’s not really saying that someone with prostate cancer has a 99% chance of surviving for five years, because there’s always a chance they’ll die from something else during that time, like heart disease, a car accident, or hippopotamus attack at the local zoo. It’s saying that if a comparable “healthy” population has 100 people who don’t have heart attacks and survive trips to the zoo, etc. for five years, that you would expect 99 people who have prostate cancer to also be alive at the end of that, even after accounting for all the heart/hippo attacks that killed people who had prostate cancer, too. For comparison, breast cancer has a 90% five year relative survival rate, and lung cancer has an 18% rate. [3] The 10 year rate for prostate cancer is 98% and the 15 year rate is 96%. Because prostate cancer’s survivability is so high, and because prostate cancer is typically found in people older than 65, the majority of people who are diagnosed with prostate cancer die of something else first.

Furthermore, the National Cancer Institute has a breakdown of five year survivability, based on the stage of the prostate cancer. The stage is basically a measure of how bad the cancer is or how much it has spread. The types they report are “localized”, “regional”, or “distant”. Localized means that the cancer remains within only the prostate. Regional means that the cancer has spread to parts of the body right near the prostate, such as the seminal vesicles. Distant means that the cancer has spread well beyond the immediate neighborhood of the prostate. 79% of prostate cancer cases are localized, 12% are regional, 5% are distant, and 4% are of unknown severity. According to the NCI, local and regional cases have a 100% five-year survivability, which essentially means that people do not die from prostate cancer as long as it remains local or regional. If the cancer reaches the distant stage, five-year survivability drops dramatically to only 29.8%. But again, that’s only around 5% of cases. [4]

On top of this already high survivability rate, cancer in general is becoming more survivable. New treatments are being developed, meaning that for someone diagnosed today, their 15 year survival rate will likely be better than someone diagnosed in the past. Over time, there may even be a cure or a vaccine developed, which can completely eradicate prostate cancer. Someone who is 20 today might not even have to worry about getting prostate cancer by the time they’re over 65. (Of course, there’s also the flip side, which is that as medical science gets better, more effective treatments are developed for other diseases and health problems, too, and people live longer in general. So someone who survives a heart attack at 70 that would have killed them just ten years ago now may live until prostate cancer can kill them at 102.)

Now, don’t get me wrong. Cancer is an awful, horrible thing in all its forms, including prostate cancer. Dying from prostate cancer leaves someone just as dead as dying from lung cancer. These statistics and survivability rates don’t change it’s ability to destroy a life.

The American Cancer Society does not recommend routine screening for people with an average risk of prostate cancer. This is because finding the cancer early does not significantly improve survivability, and because treating the cancer can cause issues (like incontinence and impotence) which can actually be worse than the cancer. As one doctor put it, “Evidence of harm from prostate cancer screening is stronger than evidence of benefit.” [5]

It should be noted that prostate cancer rates vary notably by race. Black people are twice as likely to get prostate cancer and twice as likely to die from it than white or Hispanic people. White or Hispanic people are about 50% more likely to get prostate cancer than Asian/Pacific Islanders or Native Americans. [6]

Nobody knows what causes prostate cancer. Some cancers have a clear causal link to a risk factor. For instance, smoking is responsible for 80% of lung cancer deaths. If you avoid smoke (and asbestos and radon, to lesser extents), you’re far, far less likely to develop lung cancer. There’s nothing like that for prostate cancer. Doctors can’t say “don’t do X and you won’t get prostate cancer”. There are many theories, from hormonal interactions, to STIs, to a vitamin D deficiency, to the “prostate stagnation hypothesis” which basically says that prostate fluid goes bad over time and that it won’t go bad if the system is regularly flushed. Neither of the papers I read are explicitly looking for the cause, instead, they are looking for an association between the frequency of ejaculation and the incidence of prostate cancer, which can then be used to guide further exploration into the causes.

The Studies

The two papers I read were “Ejaculation Frequency and Subsequent Risk of Prostate Cancer” by Leitzmann, et al (JAMA, 2004) [7], and “Ejaculation Frequency and Risk of Prostate Cancer: Updated Results with an Additional Decade of Follow-up” by Rider, et al (European Urology, 2016) [8]. These seem to be the source of the idea that frequent ejaculation prevents prostate cancer. Both of these papers use data from a long term cohort study called the “Health Professionals Follow-up Study” [9], which I’ll talk about more in a moment. Rider 2016 is a similar analysis to Leitzmann 2004, but it looks at an additional decade of data from the cohort study.

The overall conclusion of Leitzmann 2004 is “Our results suggest that ejaculation frequency is not related to increased risk of prostate cancer.” Notice that this only says that increased ejaculation frequency doesn’t have anything to do with increased risk. They’re not saying that it decreases the risk, only that it doesn’t make it worse.

The overall conclusion of Rider 2016 is “These findings provide additional evidence of a beneficial role of more frequent ejaculation throughout adult life in the etiology of PCa, particularly for low-risk disease.” The “low-risk disease” part is important. As I’ll get into more in a bit, their results around advanced or lethal forms of prostate cancer are mixed.

Both papers use data gathered from the “Health Professionals Follow-up Study”. This study is a long term, recurring survey, following a cohort of male doctors aged 40-75 that were selected for the study in 1986. (There is a similar study including women, called the “Nurses’ Health Study”.) The goal of this study is to track the long-term health of these participants. No one can be added to this study, it will be the same group of people until there are no more people who respond. If a participant dies, they are not replaced in the study. In fact, that death is a valuable data point. Every two years, participants are sent a follow-up survey, and that information is compiled and can provide a long term view of the health and lifestyle of a particular individual.

The makeup of the cohort is important. The study designers selected health professionals, because they believed that people working in that field would be more likely to recognize the importance of such a study and be more compelled to diligently follow up and provide accurate information. However, it needs to be recognized that such a selection will introduce a huge bias in the population sample. Health professionals are likely to have a higher than average income. They’re probably less likely live next a chemical factory or breathe the air in a mine for long periods of time. They’re probably more likely to take better care of their health overall. And since nearly 20% of this cohort were veterinarians, they are probably far more likely to be attacked by a hippopotamus at the zoo than you are.

The cohort is also overwhelmingly white. Like greater than 91% white. When you’re talking about a disease that strikes black people twice as often as white people, your results are questionable when only about 1% of your sample is black. In fact, Leitzmann 2004 acknowledges this: “Our results are generalizable to white US men aged 46 years or older.”

So, basically, the HPFS is skewed heavily towards healthy high-middle to upper class white people. It’s possible that this bias has no material impact on the results, and it’s also possible that the bias can be controlled away, but it is important to note that this is skew is present as it has the possibility that it will render the findings invalid for a general population. Both papers recognized this bias and attempted to control for it.

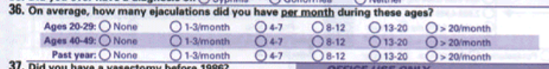

In 1992, the HPFS asked study participants about their frequency of ejaculation for three time periods in their life: Between ages 20-29, ages 40-49, and in the year before the survey regardless of age (which would have been 1991). Here is the question asked by the HPFS, as seen on the survey form [10]:

There were several possible issues noted with asking this question. First, it’s a bit of a sensitive question. The researchers believe that the anonymous nature of the responses should help with the accuracy of the results. Furthermore, the section of the survey was preceded by an acknowledgement of the sensitivity of the questions and an explicit invitation to skip any questions the participants did not wish to answer. While this likely further enhances the truthfulness of the responses, there is no way to know who did not answer and whether or not that alters the results of any analysis of this data. Was it the crowd who would have answered “None”, but were so put off by the questions that they skipped the section? Or was it people too embarrassed to admit their two-to-three times a day habit? Or was it a more even distribution that proportionally left out people in all categories? There is also a concern regarding “recall bias”, in other words, that people were remembering things wrong, largely because time had passed. In 1991, the participants were age 45-80, meaning that “20-29” was a long time ago for most of them, and they might not have a clear memory of the number of times they ejaculated in a given month. Also, some of the participants were still in their forties when this question was asked, so their Ages 40-49 may be inaccurate, and the “Past Year” answer would overlap with that time frame.

For reference, the following table summarizes the percentage of the study population that falls within each “Ejaculations Per Month” (EPM) range, based on the “Lifetime Average” calculated in Leitzmann 2004, for a total of 29342 people.

| 0-3 EPM | 4-7 EPM | 8-12 EPM | 13-20 EPM | 21+ EPM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1327 | 6523 | 9107 | 10362 | 2023 |

| Percent | 4.5 | 22.2 | 31.0 | 35.3 | 6.9 |

A couple of things to notice here. First, the percentages don’t add up to 100 because of rounding. Second, 13-20 had the highest number of people, while 0-3 was the lowest. 21+ wasn’t that much higher than 0-3.

Also, notice that these numbers group 0-3 together into a single bucket, despite the original question having separate options for “None” and “1-3”. Why? Because they claim that there weren’t enough people who reported “None” to be able to analyze them as a separate group. While I can understand that decision from a mathematical point of view, I am frustrated by it, because I’d like to know what percentage of people actually reported “None” and also because the “None” category is of very critical importance to aces who are attempting to use these findings to decide whether or not to masturbate. Neither paper examines the None group. In fact, both papers tend to brush aside the 0-3 category entirely. (More on that in a bit…)

The papers attempt to calculate the relative risk or the hazard ratio of each group. “Relative Risk” (RR) or “Hazard Ratio” (HR) are a way to compare two groups that are similar except for the variable you’re interested in comparing. This lets you see whether that variable has an impact on what you’re interested in. An HR or RR of 1.0 means that there is no difference between the baseline and the comparison group. An HR or RR of 0.5 means that the comparison group is half as likely to be impacted than the baseline group, while an HR or RR of 2.0 means the comparison is twice as likely to be impacted. In this case, lower is better, higher is worse.

That last paragraph probably didn’t make a whole lot of sense to anyone who didn’t get at least a math minor in college, so let’s look at an example. Leitzmann 2004 reports that the RR for the 21+ EPM (Ejaculations Per Month) group is 0.89 when compared to the 4-7 EPM group. What this means is that people who ejaculated 21 or more times per month on average are only 89% as likely to get prostate cancer than people who only ejaculated 4-7 times per month, or that they’re 11% less likely to get prostate cancer.

11% less likely! That sounds pretty good, right? Case closed, let’s tell everyone with a penis to get cranking! Y’all got some work to do!

This is what mainstream coverage of these studies ends up reporting. But this isn’t the end of the story. Not by a long shot. Let’s look at the rest of the numbers.

It’s not saying that the overall risk of getting prostate cancer is cut by 11 percentage points. Since the overall risk is about 11.1%, cutting it by 11 points would leave only a 0.1% chance behind. That would be a huge, very substantial difference! But that’s not what it means. It actually means that it drops the risk by 11% of that 11.1%, which means the overall risk of getting prostate cancer would go down by about 1.2%. That would still mean someone has a 9.9% chance of getting prostate cancer.

The following table gives the HR or RR from both studies for each group and for each age range. (For simplification, I am using the “Multivariate RR” values from Leitzmann 2004 and the “Multi-variate non-Erectile Dysfunction HR” values from Rider 2016 for this table.)

| Study | 0-3 EPM | 4-7 EPM | 8-12 EPM | 13-20 EPM | 21+ EPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leitzmann, Age 20-29 | 1.09 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

| Rider, Age 20-29 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| Leitzmann, Age 40-49 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.68 |

| Rider, Age 40-49 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

You may have already noticed the column that’s full of 1s, and thought “That’s weird”. That is because of how those HRs and RRs are calculated. You have to pick one of the groups as the reference baseline, and compare all of the other groups to it. Both papers picked the 4-7 EPM group as the baseline, so when you compare the people in 4-7 EPM to themselves, you get a 100% match, therefore you get an HR or RR of 1. The numbers for all of the other groups are comparing the likelihood that someone in that group will get prostate cancer compared to the likelihood that someone in the 4-7 group will get prostate cancer.

But… Hang on a second here. They chose 4-7 EPM as the baseline? If you’re trying to determine whether or not more frequent ejaculations changes the risk of getting prostate cancer, shouldn’t you start with the lowest value, and go up from there? Why would you pick a group in the middle to compare everyone against?

Leitzmann 2004: “We used the category of 4 to 7 ejaculations per month as the common reference group to achieve meaningful comparisons between increasingly extreme ejaculation frequencies and to ensure stability of the RR estimates.”

Rider 2016: “As in the 2004 report, 4–7 EPM was selected as the reference category as relatively few men reported an average of 0–3 EPM.”

In other words, Leitzmann 2004 picked 4-7 because it made their numbers better, while Rider 2016 picked 4-7 because Leitzmann did and also because they felt there weren’t enough people in the 0-3 category.

Making better numbers is also what leads to the “multivariate” and “non-ED” classifications. The researchers consider additional data and adjust for it or completely remove those data points from the calculations. For example, the “non-ED” category in Rider 2016 excludes participants who had reported having erectile difficulties. The paper explains that this group was excluded because ED is likely to cause lower ejaculation frequency and tends to be associated with other conditions that can lead to early death. Since prostate cancer is typically found in older people, if someone dies early, they’re less likely to get prostate cancer and have it diagnosed. So that exclusion could be considered a legitimate way to filter out bad data that will muddle your findings.

Or… It can be seen as an arbitrary way to make your findings appear more conclusive. If you get rid of people with ED, It could also be argued that perhaps you should eliminate smokers with a vasectomy because, hey, they got that vasectomy for a reason (wink-wink) and they’re probably going to die of lung cancer. Splitting up your data in a way to make your numbers look better (Whether deliberately or unconsciously) is called “p-hacking”. P-hacking happens because people like clear conclusions. In particular, journal editors like clear conclusions. If you write a paper where you say “I looked at all this data and didn’t find anything”, that’s a valid scientific result, but it’s not as interesting as writing a paper that says “You’re less likely to get prostate cancer if you ejaculate more”. Rider 2016 was accused of p-hacking [11], although they did provide a rebuttal to these claims.

You may also be wondering why the Leitzmann and Rider numbers are so different. The Rider paper was looking at the same people as the Leitzmann paper, so shouldn’t they be the same? Remember that the Rider paper used an additional ten years of followup data to consider. In those additional ten years, the number of study participants who were diagnosed with prostate cancer had roughly doubled. And remember that this is a cohort that doesn’t change, so the number of cases will never decrease. Once someone gets prostate cancer, they will never “un-get” prostate cancer for the purposes of this study, even if they undergo treatment that leaves them cancer-free. At the same time, since much of the cohort is still alive, there are quite a few of them who will be diagnosed at some point in the future. Rider 2016 looked at the HPFS data from 2014, when the youngest members of the cohort were 68. Recall that most cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed after age 65. So these numbers are a work in progress. They will continue to change until the entire cohort is deceased.

Anyway, enough about the methods… What do those numbers even mean?

It’s quite a ways back up the page now, so I’ve repeated the table of interest here, so you don’t have to keep scrolling around.

| Study | 0-3 EPM | 4-7 EPM | 8-12 EPM | 13-20 EPM | 21+ EPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leitzmann, Age 20-29 | 1.09 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

| Rider, Age 20-29 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| Leitzmann, Age 40-49 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.68 |

| Rider, Age 40-49 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

Recall that lower is better and higher is worse, and a value of 1 means there’s no difference. So yes, looking at that table, the data indicates that 21 or more ejaculations a month does have a lower risk than only ejaculating 4-7 times a month. But 13-20 is also better. 8-12 is better in all but one of the categories. But… Hold on a minute. 0-3 is also better in most of the categories? That doesn’t really fit with the theory that ejaculating more leads to less prostate cancer. You’d expect 0-3 to be higher than 4-7 if that were clearly the case. In fact, based on this table, the conclusion you should draw is that people should avoid ejaculating 4-7 times per month, and instead go for more or less, because 4-7 is clearly the worst for your health.

Or… Not.

You see, all of these numbers also come with a “Confidence Interval”. You can think of the confidence interval (or “CI”) as being similar to the “margin of error” of a survey. You’ve probably heard of a survey where they’ve said a political candidate is polling at 51% of the vote, with a margin of error of +/- 3%. That means that the actual support for that candidate is probably somewhere between 48% and 54%. That 48%-54% range is the confidence interval. In most cases, including in these papers, the CI used is the “95% Confidence Interval”, which means that the correct value of an estimated number is between the high and low numbers 95% of the time. In other words, when the Leitzmann paper reports a value like 0.89, with a CI of 0.73-1.10, what that means is “I’m 95% sure that the real value is between 0.73 and 1.10, and I think it’s probably somewhere close to 0.89.”

Now, imagine if I said “I’m 95% sure that my wallet has between $7.30 and $11, and I think I have around $8.90”. That’s almost a $4 difference between my high and low estimates. You’d be rightfully worried about my ability to pay my $8.50 share of the cab fare, because maybe I really only have $7.30. And if the cable company told you that they were 95% sure that the repair tech would be at your place between 7:30 AM and 11 AM, but probably around 8:50 AM, you’d be awake and dressed by 7 and you’d clear your calendar until noon. But if these confidence intervals were narrower, like if I said I had somewhere between $8.85 and $8.95, or that your cable is getting fixed between 8:40 and 9:00 AM, you’d feel a lot better about those estimates.

So let’s include the confidence intervals in that table, then see what it says.

| Study | 0-3 EPM | 4-7 EPM | 8-12 EPM | 13-20 EPM | 21+ EPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leitzmann, Age 20-29 | 1.09 (0.80-1.47) | 1 | 1.06 (0.88-1.29) | 0.95 (0.78-1.16) | 0.89 (0.73-1.10) |

| Rider, Age 20-29 | 0.91 (0.71-1.17) | 1 | 0.99 (0.86-1.13) | 0.90 (0.78-1.02) | 0.80 (0.69-0.92) |

| Leitzmann, Age 40-49 | 0.83 (0.64-1.09) | 1 | 0.96 (0.80-1.16) | 0.98 (0.79-1.13) | 0.68 (0.53-0.86) |

| Rider, Age 40-49 | 0.91 (0.75-1.11) | 1 | 0.93 (0.84-1.02) | 0.81 (0.72-0.90) | 0.82 (0.70-0.96) |

What it says now is “That’s a hell of a lot of numbers”. If you turn your head and squint just right, maybe you can start to see a lot of the numbers are now bigger than 1. But it’s all still largely a jumble. So let’s make it easier to see what’s going on.

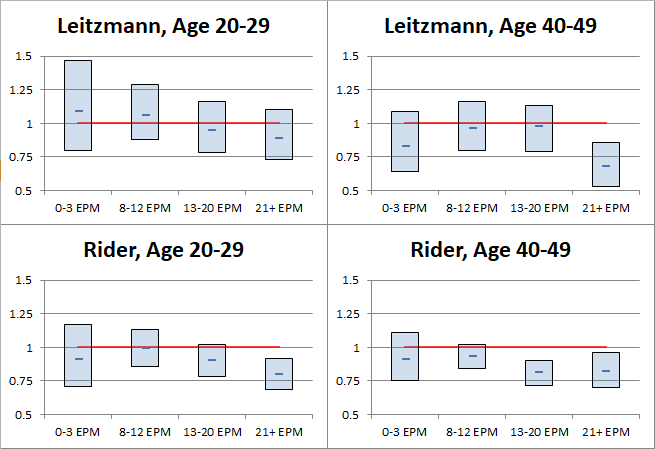

Okay, yeah, so it’s still a bit of a jumble, but now it’s one with pretty boxes and lines and things.

The boxes indicate the extent of the confidence intervals for each group and the dash in the middle of each box is the estimated HR/RR. The actual value is probably somewhat close to the dash, but not guaranteed to be. There is a 95% chance that the actual value is within the extent of the box, and a 5% chance that the actual value is outside the box entirely. The red line at 1 represents the 4-7 EPM reference category that everything else is compared against. If a box or a data point is above the red line, that indicates that the HR/RR is greater than the reference and that the likelihood of prostate cancer may be higher for that group than it is for people who ejaculate 4-7 times per month. If a box or a data point is below the red line, that indicates that the HR/RR is less than the reference and that the likelihood of prostate cancer may be lower for that group than it is for people who ejaculate 4-7 times per month. If the box straddles the line, that means that the risk could be higher, could be lower, and you can’t say with statistical confidence that which side it’s actually on.

As you can see, almost all of those boxes straddle the line. In other words, most of those boxes tell you very little about whether or not the risk of prostate cancer is truly higher or lower for those groups. What once looked like a clear sign that you should avoid ejaculating between 4-7 times a month has turned into a bit of a mathematical ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

There are a few of the confidence interval boxes that are completely below the red line. That means that the data analysis is at least 95% sure that there is actually a reduction in the risk of prostate cancer for those groups. The only group that’s below the red line in both studies is the group that ejaculated more than 21 times per month at age 40-49.

So… The conclusion that’s drawn from this is that it doesn’t matter what you do the rest of the time, but you’d better get busy in your 40s? As I noted earlier: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Recall that the two studies are the same group of people, just with ten additional years of data included in the Rider paper. The confidence intervals are getting narrower, which is what you’d expect as you get a larger sample size. But outside of that, some of the numbers vary wildly between Leitzmann and Rider. Comparing the Age 40-49 data between the two papers, it appears that the RRs for the 8-13 and 13-20 groups get much better, while 21+ takes a sharp turn for the worse. The surface level implication there is that if someone ejaculates between 8 and 20 times per month, then they either get it earlier than someone with 21+ EPM or they don’t get it at all, and that the 21+ EPM group might delay the onset of prostate cancer for a few years, but eventually catches up?

But that doesn’t really make much sense… So also recall that the data from the cohort is a work in progress. Maybe it really is just random and the numbers look kinda weird because there’s absolutely no correlation between ejaculation and prostate cancer. Surely, these aren’t the only two papers that explore this potential link. Unfortunately, I don’t have time to explore the literature and see what they all have to say.

Fortunately, Leitzmann and Rider already did that for us! Leitzmann, take it away!

Previous investigations on reported ejaculation frequencies or sexual intercourse and prostate cancer are limited to studies of retrospective design and results are mixed. Nine studies observed a statistically significant or nonsignificant positive association; 3 studies reported no association; 7 studies found a statistically significant or nonsignificant inverse relationship; and 1 study found a U-shaped relationship.

That’s all sciencey talk, but the key phrase is “results are mixed”. Leitzmann 2004 reviewed 20 different studies that look at a possible link between ejaculation or intercourse (which implies likely ejaculation) and prostate cancer and they all said different things.

Also, that paper is from 2004, so it’s missing 14 years (as of this writing) of additional research that has likely been conducted in the meantime. Rider 2016 looks at a handful of additional studies, and is more to the point:

The literature exploring the role of sexual activity in the etiology of PCa is inconsistent.

“Inconsistent.” “Results are mixed.” That is hardly wide-ranging compelling evidence in favor of the theory that more frequent ejaculations will decrease the risk of prostate cancer. Or that prostate cancer risk has anything to do with ejaculation at all.

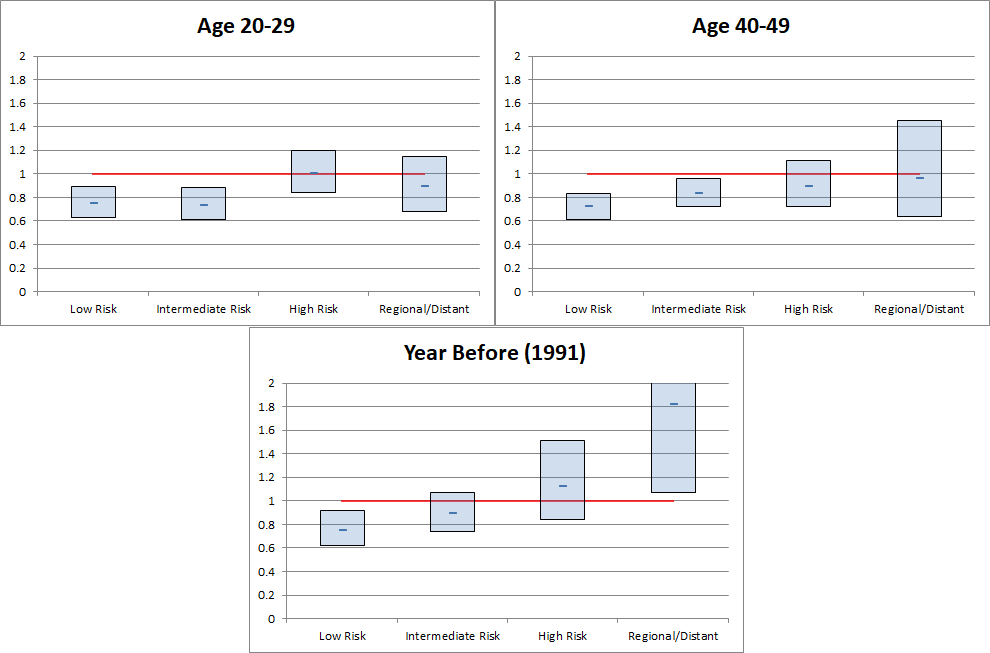

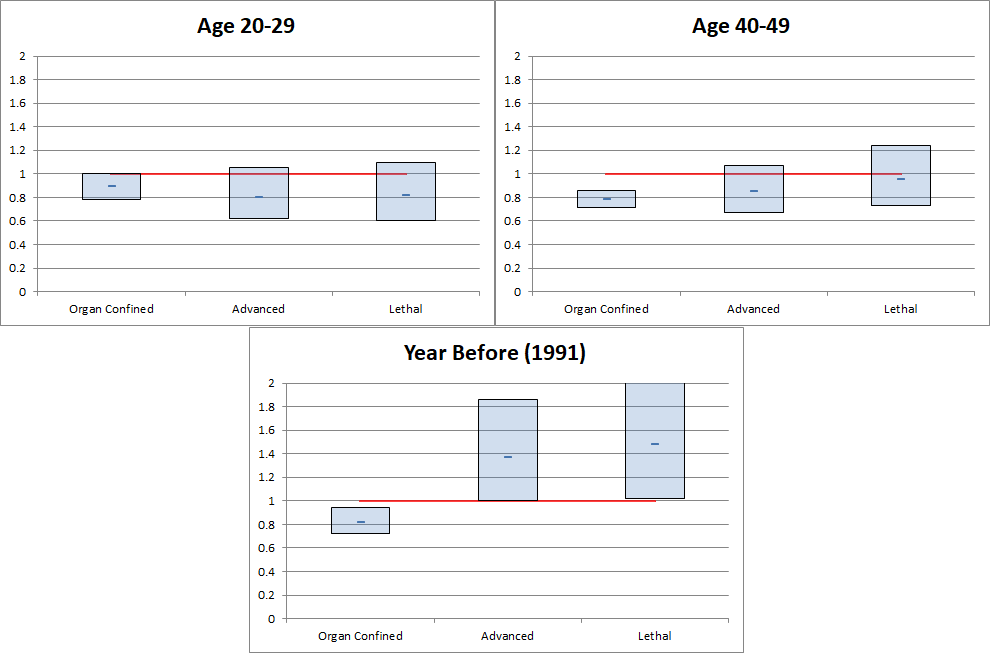

But okay, let’s set all those questions and doubts aside for the moment and assume that Leitzmann and Rider are correct, that there is a statistically significant correlation here, that as ejaculations per month go up, prostate cancer goes down. But does that actually make a difference in how bad the disease is? Remember back when I was talking about the survivability of prostate cancer, how I mentioned the different stages, local, regional, and distant? And how local and regional had a 100% five-year survivability rate, according to the National Cancer Institute? So, does more frequent ejaculation decrease the risk of the more lethal distant stage of prostate cancer?

No.

Sorry, got ahead of myself there. But no, no it doesn’t. At least not according to these papers.

I present Rider 2016’s numbers here because that paper has an additional 10 years of data over Leitzmann 2004. (Some of Leitzmann’s numbers are just plain wacky due to lack of data. For instance, one of the categories has an RR CI of 0.49-6.60, which is like saying “The risk could be cut in half or it could be 6.5 times worse. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯” Leitzmann’s numbers are generally similar to Rider’s, however.) Rider breaks down the numbers by risk category and stage. I have included only the data for only the 13+ EPM group (Rider combines the 13-20 and 21+ groups for this analysis because there were not enough cases in the 21+ group in some of these categories for the data to be meaningful).

There are three main conclusions that can be drawn from these tables.

- A person who ejaculates more than 13 times per month has a lower chance of low risk or organ confined prostate cancer.

- A person who ejaculates more than 13 times per month has a potentially greater chance of higher risk or advanced/lethal prostate cancer.

- OMG, 1991 is gonna kill everyone!

If 1 and 2 are true, think about what that means for a moment. Someone who ejaculates more frequently is less likely to have the lower risk, less fatal types of prostate cancer, but they’re more likely to get the type that will kill them. That, on its own, doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Prostate cancer is not a “Do Not Pass Go, Do Not Collect $200” sort of thing. You don’t just skip to the advanced/distant stage of the disease. If there’s an increased risk of the more deadly types of cancer, then those deadly cancers had to progress through the earlier stages, so there should be an increase in the earlier stages, as well.

There are a couple of possible explanations for this. First, the p-values for these findings that suggest an increase are fairly high. A “p-value” is a measurement of how likely it is that the results you got are simply due to random chance. The higher a p-value is, the more likely a result is random, while the lower it is, the more likely your result is valid. You can think of a p-value as sort of how confident you are in your confidence. It’s generally accepted that a p-value < 0.05 means your results are statistically significant, because it means that there’s only a 5% chance that your results are random. (Side note: The p-value is the same p in the “p-hacking” that I mentioned earlier. p-hacking is the process of trying to manipulate your data and analysis to find something that yields p < 0.05. The problem is that in order to do so, you may have manipulated your data into meaninglessness.)

Another possible explanation is that people who ejaculate 13+ times per month really like doing it. Also, everyone in this study is a health professional, so they’re likely to know that treatment for prostate cancer often leads to impotence. So, perhaps they intentionally skip prostate cancer screening or treatment to avoid a diagnosis and the possible consequences. But if this is true, this actually would invalidate the other findings, too, specifically that a higher EPM rate is associated with a decreased risk of prostate cancer. The risk might not actually be lower, instead, those people just might not know that they have it.

As for 1991 killing everybody, that is actually a legitimate finding. The p-value for that set is 0.05, so it’s statistically significant. In fact, that’s a point of consternation for Rider 2016, which apparently makes up a symptom for prostate cancer that somehow encourages more frequent ejaculation to explain it. I mean, I’m all for hypothesizing on possible causes when your data doesn’t match reality, but… If you have to immediately say “While we are not aware of any literature supporting [this]” after your proposal, you probably shouldn’t be saying it. Especially when it seems like it’s something that should be easy for a urology researcher to verify one way or the other. Walk into the break room and say, “Hey, any of you all ever hear of people wanting to get off more when they have prostate cancer?” If the answer’s “yes”, then add a line about how there’s unverified anecdotal evidence in support of the idea and you’ve got the topic of your next paper. If the answer’s “no”, drop the idea and admit you don’t have an explanation.

Look at what they’re saying there, though. They’re speculating that the development of prostate cancer might influence the frequency of ejaculation, when all this time, the focus has been on whether frequency of ejaculation might influence the development of prostate cancer. I want to return to something I said earlier, that no one really knows what causes prostate cancer. So even if there is a statistical correlation between ejaculation frequency and prostate cancer, that’s not necessarily an indication that it’s a causal relationship. If it’s “prostate stagnation” that causes prostate cancer, then yes, there’s a causal relationship, where ejaculation flushes the toxins out which prevents cancer. But if it’s a lack of vitamin D, then no, there’s not a causal relationship, because it’s just vitamin D making people more horny AND preventing cancer. And if that’s the case, you can just take vitamin D supplements and get the cancer reduction benefits, and however much you ejaculate doesn’t matter. Neither paper is attempting to prove a cause of prostate cancer, and neither paper claims a causal link. They are only looking to see if there is a relationship.

Okay, okay, okay. Let’s take a step back and refocus on what we’re actually interested in. Let’s assume that there actually is a causal relation between more ejaculations and less prostate cancer, and let’s ignore the suggestion of a possible increase in the higher risk types of cancer associated with more ejaculations. Going on the pure optimistic, best case scenario here, what I want to know is this: How much does the risk of prostate cancer actually go down if I ejaculate more frequently?

I have no idea.

None at all. The papers don’t actually say. None of these RRs and HRs and confidence intervals and other things being thrown around actually give that number. What they all say is that the risk may be lower for the 21+ EPM group when compared to the 4-7 EPM group. But what’s the risk for the 4-7 EPM group? Are they higher than the average risk? My mathematical sense about how averages and populations samples work says that yes, they are higher risk than average. If the 4-7 group is considered the baseline reference of 1, and if all the other groups are less than 1, then the 4-7 group has to have an above average risk in order for the lower relative risks of the other groups to balance out.

There may be enough data available in the papers to try to come up with some sort of rough estimate, though. I’ll warn you now that the following is speculation and likely mathematically unsound, but at this point, we’re already ignoring so many red flags and possible issues, so what’s one more thing to overlook, eh?

For this, I’m going to look at the overall risk of prostate cancer, compared to the incidence in the overall study population, and for each of the EPM groups as reported in Rider’s Age 40-49 category.

| Overall Population | Study Sample | 0-3 EPM | 4-7 EPM | 8-13 EPM | 14-20 EPM | 21+ EPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.1% | 12.0% | 11.2% | 13.3% | 12.4% | 10.8% | 10.3% |

The first thing that jumps out at me is that the study sample has a higher reported overall rate of prostate cancer than the general population. And remember, this is an on-going study tracking the same group of people, so that number can only go up over time. So is that difference an artifact of better health care and more detection of prostate cancer among the study population? Are dentists and veterinarians more prone to prostate cancer than other people? Or is it just ordinary sampling error? In any case, it’s notable.

Second, the 4-7 EPM group does have highest cancer rate in the study, at 1.3 points higher than the study sample rate. And 21+ does have the lowest rate, at 1.7 points lower than the sample rate. (It’s worth pointing out that the 0-3 group is also lower than the overall study rate.) What that means is that if there is a reduction in cancer risk for 21+ EPM over 4-7 EPM, you lose about half of the effective value of that reduction, just to get back to the study rate.

Another way to think of this is to imagine a store advertising a 30% off sale. 30% off, that sounds great! But if their original prices are 13% higher than the store next door, then you’re not actually getting a 30% discount, you’re really only saving 17%. And if all the stores in that city already have a 9% higher sales tax than the rest of the state, that eats into that 30% discount even more. At the end of the day, maybe you’re only getting an 8% discount. Still a discount, sure, but hardly what was advertised, and it’s now low enough to make you think twice about going out of your way to shop there.

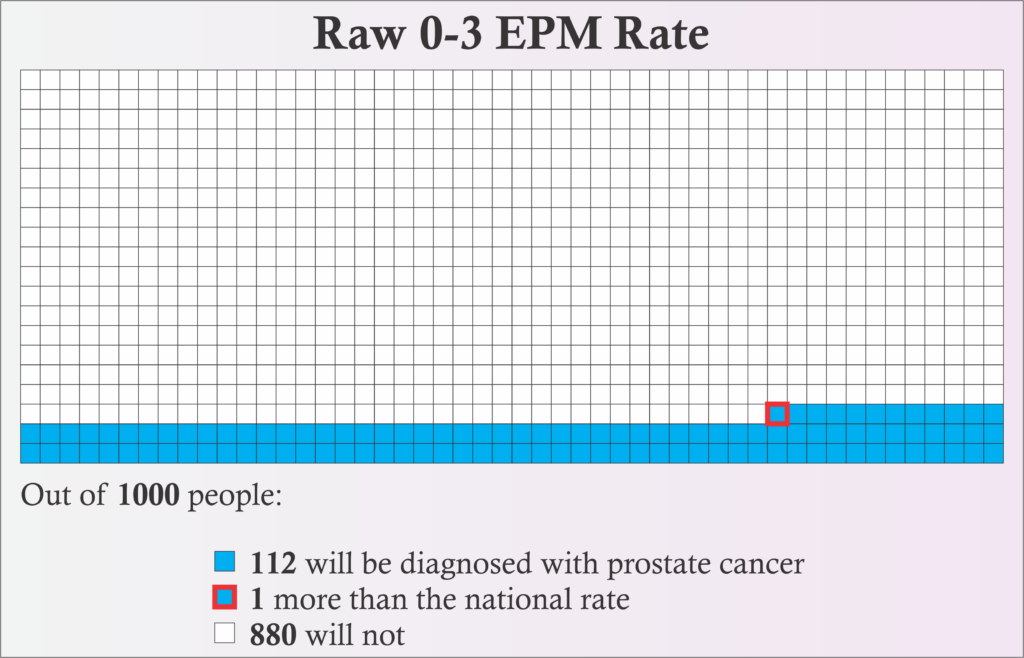

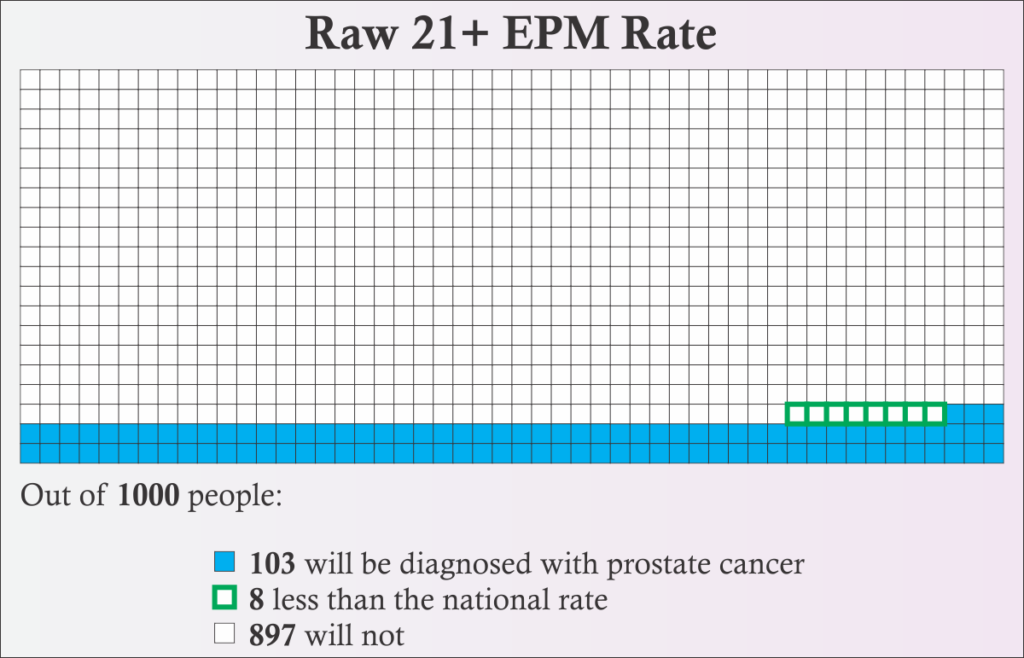

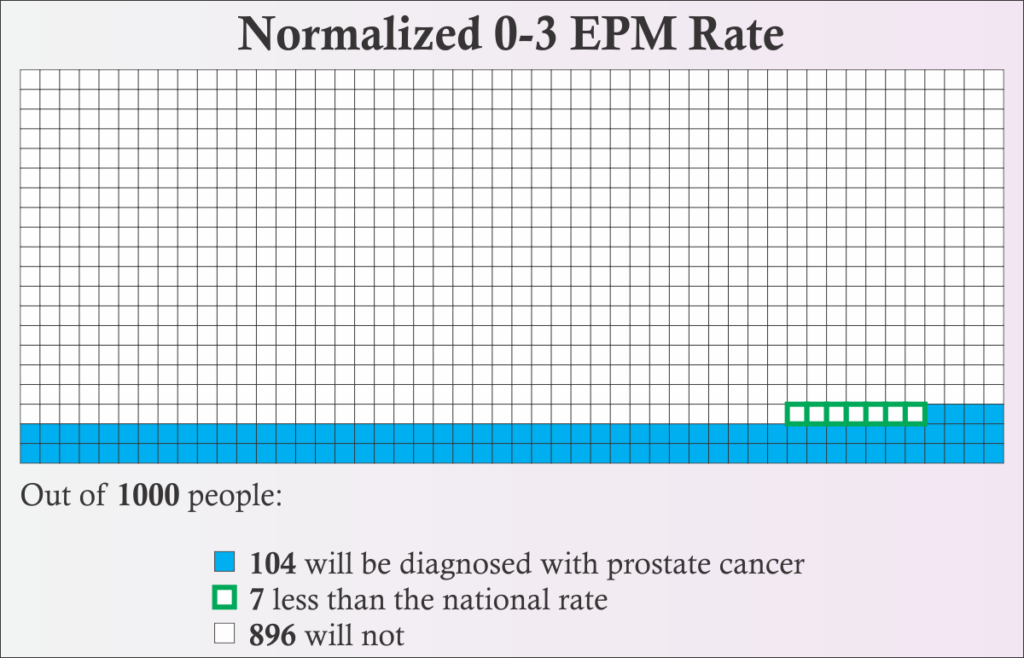

However, an 8% discount is still a discount, so let’s look at what kind of discount you might actually get. Let’s go back to that room of a thousand prostate-owning people for one final batch of comparisons. (We’ve left them sitting in there for so long, it would be rude to keep them waiting any longer.) For this, I’m going to compare the absolute difference between the national prostate cancer rate compared to the raw 0-3 and 21+ study group rates, as well the deltas for those groups compared to the study rate normalized to the national rate.

(And have I mentioned that what I’m doing here isn’t sound. Because what I’m doing here isn’t sound. If you try to quote anything that I’m about to report in this section as some sort of legitimate finding, then you’ve completely missed my point and should start over at the beginning.)

| Overall Population | Study Sample | Raw 0-3 EPM | Raw 21+ EPM | Normalized 0-3 EPM | Normalized 21+ EPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.1% | 12.0% | 11.2% | 10.3% | 10.4% | 9.5% |

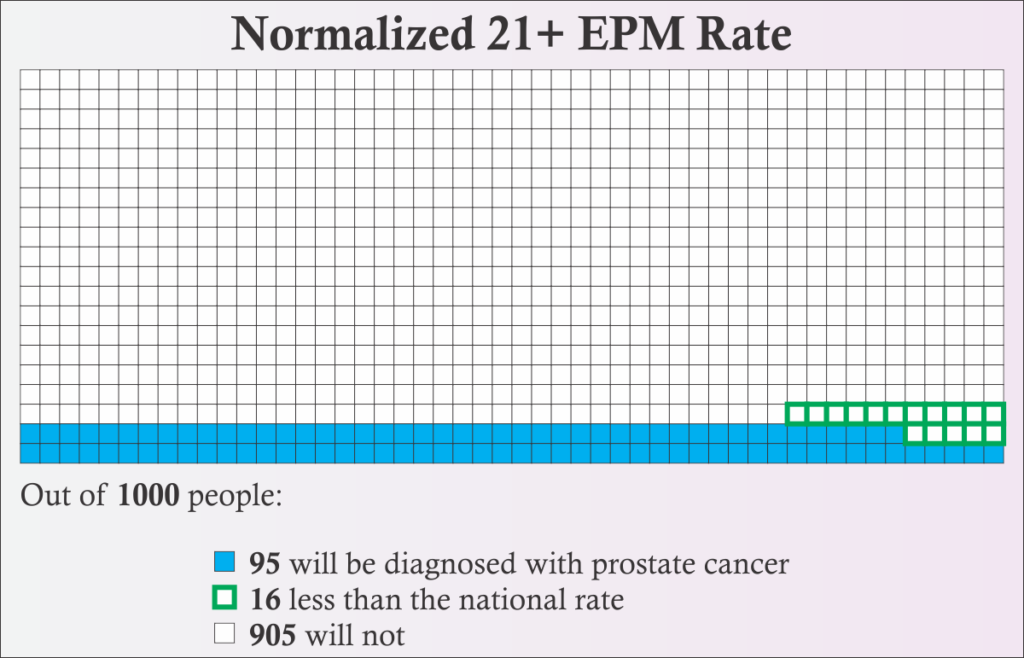

In Figures 9-14, I’ve highlighted the difference from the national rate. Filled boxes with red borders are an increase over the national rate. Empty boxes with green borders are a decrease compared to the national rate. I have one final observation to make:

The “Normalized 21+ EPM Rate” represents pretty much the best of the best of the best case scenario. [Figure 14] Getting there required ignoring pretty much every concern we’ve come across, deliberately selecting the best data set, and probably ended up making statisticians scream “What are you doing?!” at their screens. And even with all that, the difference is only 16 boxes with green borders. That means that even if the papers were accurate AND there really is a causal link between ejaculation frequency and reduced risk of prostate cancer AND all the leaps of mathematical faith we took are correct AND medical science doesn’t change at all in the next couple of decades AND no one else in the study cohort gets prostate cancer AND you dedicate yourself to jacking off at least 5 times per week for the rest of your life, the best result is a 1.6% chance that something in your life will turn out different.

I’m not gonna drive across town for that sale.

Conclusion

First off, thanks for sticking with me through thousands of words of math and science and graphs and stuff. Or thanks for scrolling past all of that and skipping directly here. Whichever.

Let’s review the key points that we’ve learned.

- You’re probably not going to get prostate cancer, no matter how much you ejaculate. There’s an 89% chance you won’t.

- Even if you get prostate cancer, it’s probably not going to kill you. If you get prostate cancer, there’s an 80% chance that you’ll die of something else, and its 15-year survivability rate is 96%, so even if it does kill you, it’s probably going to take its time.

- Because medical science is continually improving, prostate cancer gets less likely to kill you all the time.

- Studies involving sexual activity/ejaculation and risk of prostate cancer are “mixed” and “inconsistent”.

- There is no proof that ejaculation itself decreases the risk of prostate cancer. At best, these papers may have found a correlation, but correlation is not causation. At worst, some other papers have reported that there may be an increased risk of cancer associated with more frequent ejaculation.

- The papers do not report an absolute reduction in risk for more frequent ejaculation, only a relative reduction when compared to the 4-7 ejaculations per month group. The overall potential benefit is unclear.

- My best-case, super-optimistic, ignoring-all-problems-and-red-flags, everything-is-perfect, don’t-quote-me-on-this analysis indicates that there might be at best a 1.6% chance that you’ll avoid getting prostate cancer by masturbating at least 21 times a month.

- Both papers basically ignore the 0-3 EPM group, which happens to be a group of interest to asexual people, especially those who only masturbate because they’ve heard it can decrease the risk of prostate cancer. They don’t even consider the risk of prostate cancer in people who never ejaculate.

- The study the papers are based on is biased, and that bias potentially contaminates the results. The Leitzmann paper even admits that the results are only useful for white guys over the age of 40 in the US.

- The findings suggest that all levels of ejaculation frequency other than 4-7 EPM (including 0-3) may have a lower risk of cancer than those in the 4-7 EPM group.

- There is only a statistically significant decrease in the risk of prostate cancer in both papers for the group who ejaculated 21+ times per month at age 40-49.

- 21+ ejaculations per month is around at least 5 times per week, which is probably waaaay more than someone who’s not a fan of the process would want to go through with it. (An informal, totally unscientific poll of aces who say they masturbate mainly to reduce the risk of prostate cancer found that most of them only do it 0-3 times per month.)

- There is a chance that ejaculating more is actually associated with a higher risk of the worst kinds of prostate cancer.

- There is a chance that the apparent lower risk of prostate cancer overall in people who ejaculate more is an artifact of a reluctance to be screened by the higher EPM groups.

- 1991 is going to kill us all. No, seriously. It was mathematically proven. See what you miss when you skip to the conclusion?

Or, to tl;dr my tl;dr:

If you’re asexual and you don’t like masturbating, but you do it anyway, only because you’ve heard that ejaculation can prevent prostate cancer: Stop. Don’t bother. You’re far more likely to die of heart disease than prostate cancer, so take that time that you would have spent masturbating, and use it doing something that’s good for your heart. (In fact, the stress of constantly doing something that you dislike is probably bad for your heart.)

And, well, if you don’t believe me that there’s essentially zero evidence that you should masturbate as a way to lower your risk of prostate cancer, take it from the authors of Rider 2016 (emphasis mine):

We wish to emphasize that until the biological mechanisms underlying this association are convincingly elucidated, interpreting ejaculation as an established means of preventing prostate cancer is premature. [12]

Sources:

[1] Key Statistics For Prostate Cancer, American Cancer Society

[2] Survival Rates for Prostate Cancer, American Cancer Society

[3] Cancer Statistics Center, American Cancer Society

[4] Prostate Cancer – Cancer Stats Facts, National Cancer Institute

[5] Prostate Cancer Screen And Detection Decline, American Cancer Society

[6] Prostate Cancer Rates by Race and Ethnicity, CDC

[9] Health Professionals Follow-up Study, Harvard School of Public Health

[10] Health Professionals Follow-up Study, 1992 Long Form Survey, Harvard School of Public Health

Asexuality and ARFID

The theme for this month’s Carnival of Aces is on asexuality and mental health. Now, ordinarily, I don’t have much to say about the topic of mental health. I’ve never been to a therapist. And that whole undiagnosed lethargic fog of depression or anxiety or whatever it is that’s going on, well, I never have much to say about that, primarily because it won’t let me say anything about it other than recurring vague posts about how I should do things that I never end up doing. But this month, one of the subprompts was to talk about eating disorders and asexuality. Now that is something I can talk about.

But before I begin, a bit of housekeeping…

Because I’m going to be talking about a topic outside of my regular subject matter, I expect this post will get some readers who are not all that familiar with asexuality. So, what is asexuality? It’s a sexual orientation characterized by a persistent lack of sexual attraction to any gender. Essentially, it’s the “none of the above” option on the sexual orientation form. You can learn more about it on this site, or over at WhatIsAsexuality.com.

And second, I am not implying that asexuality is related to any eating disorders, nor am I implying that any eating disorders are related to asexuality. I’m going to be talking about both here, and how they impact my life and how that impact is similar in some ways, but I don’t want to give the impression that I think they’re connected to each other. I also want to make clear that I’m speaking for myself here.

Also, this post is a bit… venting and angry… disordered and unfocused… That’s by design. This isn’t meant to be an in-depth exploration of what asexuality and ARFID are, or a detailed survey of the way people experience them. This is about me. And I’m angry and unfocused about this topic.

And now, the main event…

As you’re probably aware, I’m not really part of the sex fandom, as some have put it. But you may not know that I’m also not really part of the food fandom, either. I have something called “ARFID”, which stands for Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. This used to be called “SED”, or Selective Eating Disorder, but I think they changed the name because it’s less about selecting food and more about avoiding it. ARFID isn’t like one of the eating disorders you’re probably thinking of, like anorexia or bulimia, where weight or body image is at its core. Instead, it’s more of a fear of most foods, or a sense that most foods are disgusting. It’s not a matter of “I don’t really like tacos”, it’s more a matter of “Tacos are not food and that substance is not going anywhere near my mouth so don’t even try it.”

People with ARFID typically have a very limited range of foods they’ll eat. And it’s not “These are my favorite things so I eat them all the time”, either. It’s “These are the only things I am able to eat.” Things like grilled cheese sandwiches, plain pasta, macaroni and cheese, or pizza with limited or no toppings are some common (though not universal) safe foods. Sometimes it can even be very specific brands or restaurants, even though the foods are fundamentally similar between them. Like, I can’t explain why, but I love Arby’s roast beef sandwiches, but a roast beef sandwich anywhere else is not gonna happen. And it’s not always about taste. It can be about texture or presentation or some inexplicable aura of loathing. For instance, I can eat orange flavored candy and drink orange juice (no pulp), but if I try to eat an actual orange slice, my body will physically shut down in response. Rationally, I know that it tastes like orange, and I can tolerate the taste of orange (not my favorite, but it’s doable), but when I get in that situation, OH HELL NO AIN’T GONNA HAPPEN. And then I have no problem eating apples.

So, what does this have to do with asexuality? Well… Nothing. And everything.

Sex and food are two pillars that society constantly swirls around. They form the basis for the enjoyment of life for many people. Often the two are intermingled in some way (see: Hooters). And both of them are things that I am not into and that I cannot understand other people’s obsession with. But that means that I can see similarities between them, how society looks at them, and how other people treat aces and people with ARFID. That’s what this post is going to explore.

“Just try it! Maybe you’ll like it!”

This phrase is the bane of aces and … um … ARFIDers? When I talk about this in regards to asexuality, I usually make some comment about Green Eggs and Ham. In fact, my copy of Green Eggs and Ham is in with the asexuality books on my bookshelf for this very reason. But in the context of ARFID, that literally is what the plot of that book is about. Some guy does not want to eat something disgusting and gets harassed by a stranger for over 50 pages about it.

The worst part about the book is that at the end, he tries the green eggs and ham and he likes them and starts eating it on boats with goats. And so everyone thinks that’s how it works. You just try something strange and alien and you discover how fabulous it really is, and then you go around holding up signs and riding vaguely dog-like creatures and shouting at people just trying to read the newspaper about how wonderful this thing you tried is. And you shove it in their face to convince them how great it is. But that’s not how it works. That’s not how it ever works.

When I tried sex, I found it mostly boring and dull. It wasn’t some earth-rattling, life-changing transformative experience. It was repetitive, I had an orgasm, and what’s the big deal? Trying it didn’t make me like it, and certainly didn’t make me want to ride around on a dog-thing and shout at people about how great it is. But when it comes to food, it is a totally different story. New food is a nightmare. Always. It never works out. The process is something like this:

- Inexplicably decide that Food Item X is something I might actually be able to eat, despite all past experiences to the contrary.

- Food Item X sits in my freezer for weeks while I work up the courage to give it a go. 50% of new items stay at this stage until there’s an annual freezer cleaning and they get thrown out without being opened.

- I tentatively prepare Food Item X, according to its instructions.

- Food Item almost always looks or smells repulsive in some way and I wonder what in the hell I’m doing.

- I get the appropriate utensil and use it to acquire a small portion of Food Item X.

- I stare at the small portion of Food Item X on the utensil. I am paralyzed, unable to move. I typically remain in this state for ten minutes. 50% of the items which have made it this far are discarded at this point.

- I eventually work up the nerve and overcome the paralysis just enough to try tasting Food Item X.

- Food Item X is as terrible as expected. 100% of the items which reach this phase are discarded.

- I feel terrible for wasting that food.

- I feel terrible for wasting the time and energy to prepare that food.

- I feel terrible for having to waste more time and energy to prepare something else that I can eat.

- I feel terrible for generally being a failure of a carbon-based biological engine.

- And, in some cases, I feel physically terrible because Food Item X made me physically ill in some way. Sometimes for hours.

That is what happens when I “just try it”. EVERY. DAMN. TIME. So fuck you, Sam I Am. Take your signs and your weird dog thing and leave me the hell alone.

“You’re missing out!”

No. No, I’m not.

You might think that sushi is the best thing since sex or that sex is the best thing since sushi, and that there’s no way my life can be complete unless I enjoy those things equally as much as you do. But I assure you, I am not missing out on either sex or sushi. I’m not interested in those things.

We do not all have to have the same preferences. I really enjoy playing Rayman 2 for the Nintendo 64, but at the same time, I can accept that you might be living a happy and fulfilled life even if you haven’t played it. If you express an interest in video games, I might suggest that you play it. But if you tell me that you’re not interested in video games or that 3D games make you sick, I’m not going to insist that you are missing out on a fundamental piece of the human experience if you don’t play it.

So you keep your sex and your sushi and I’ll keep my Rayman 2, deal?

“It’s Just A Phase”

One of the more common dismissals of both asexuality and ARFID is that “it’s just a phase”. “You’ll grow out of it.” The idea being that pretty much everyone isn’t interested in sex or is a picky eater when they’re a kid, and that everyone will grow into a fully-developed, sex-loving, haggis-eating adult in time.

I’m pretty sure I’m old enough to know that I’m not going to start craving sexy times or Thai curry any time soon. And you should probably believe me about that.

The insidious corollary to this is that it makes people like me out to be immature and childish and objects of worthy of ridicule.

“Well, I Don’t Like XYZ Sometimes, Either”

People use this line about both sex and eating. Sometimes it’s a matter of dismissal, a way of saying “Oh, everyone’s like that, you don’t need a word for it”. Those people can just go stand on an anthill. I’m not going to waste time talking about what’s wrong with that kind of thinking. But sometimes it’s a matter of attempted sympathy, like they’re saying “well, I understand where you’re coming from, because I’m like that, too.”

Except… No, you don’t understand me.

You think sex with your husband is boring once in a while. Great. That doesn’t mean you understand what it’s like to be constantly bombarded with messages about how great sex is and how everyone loves it and should do it all the time and end up feeling broken because you can’t relate to that at all.

You don’t like lasagna. Great. That doesn’t mean you understand what it’s like to be hungry because you’re on vacation and there is literally nothing you are capable of eating at any of the restaurants in the town you’re in.

Pretty much everyone has food that they find disgusting and refuse to eat. (In fact, most people have a very limited diet, compared to what’s available in the world.) Pretty much everyone has some sexual act that they’re not into. (In fact, the majority of people automatically rule out about half of the sexual activities they could take part in, right off the bat.) But that’s not what ARFID is. That’s not what asexuality is. It’s not a “some of the time” thing, it’s an “all of the time” thing.

Unless you’re asexual or unless you have ARFID, no, you don’t understand me. So spare me the “I’m like that, too” nonsense.

“You Can’t Be, Because…”

You can’t be asexual because you masturbate! You can’t have ARFID because you eat Doritos! You can’t be asexual because you’ve had sex! You can’t have ARFID because you’ve had poutine!

Gotcha gatekeeping bullshit isn’t limited to just talking about sex or just talking about eating. I get it from both sides! People who don’t understand what something is have a way of deciding that they’re experts on a subject and feel that they need to tell me that my existence is wrong because they Know Better™.

Social Situations

Both ARFID and asexuality impact my life when it comes to social situations.

Is she flirting with me? How do I explain how I am?

Are they going to suggest dinner? How do I explain how I am?

The conversation has turned to sex. Do I have to come out and explain how I am?

The server has come by and I didn’t order anything. Do I have to come out and explain how I am?

It’s hanging out there. Everyone can see it. I’m withdrawn. I’m hiding that I’m broken. Is it safe to tell them?

Because sex is largely a taboo subject, it doesn’t come up nearly as often as food does, and that means that I’m not subjected to the same relentless taunting that I get about my eating habits. People seem to take my pulling back from conversations about sex as some sort of personal or religious objection to the topic, and they leave it alone. But when it comes to eating, it’s open season. “We’ll go somewhere they have grilled cheese for you.” “Oh look, they have cheese pizza here.” “Should we ask for the kids menu?” For some people, this is the only conversation they ever have with me. Let’s all point and laugh at the eating disorder! Fuck you, dude.

If your boss mocks you for a lack of interest in sex, you can file a complaint with HR and hopefully have that taken care of. But if your boss mocks you for an insufficiently varied diet by their standards, all you can do is laugh along through the pain.

My eating habits were also a source of extensive friction with my ex-girlfriend. I remember once she told me that she was sad that if she married me that she’d never have Vietnamese food again. So not only was I depriving her of sex, I was also depriving her of pho. Way to make me feel doubly worthless.

All this can tie back into the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (basically the psychiatrist’s bible). One of the diagnostic criteria for ARFID is “Marked Interference With Psychosocial Functioning“. One of the diagnostic criteria for MHSDD is “Clinically Significant Distress“. You could say that ARFID has caused “marked interference with psychosocial functioning”, sure. And you could say that in the past, asexuality has caused “clinically significant distress”. But you know what? Most of that interference and distress has had nothing to do with me and everything to do with the fact that people around me are assholes about it once they find out.

(And yeah, MHSDD is not asexuality, but that’s a different story…)

Alienation

Asexuality and ARFID share a sense of loneliness, of isolation, of brokenness, of being the only person like that in the world. No one understands you, there’s no way to explain it, you just don’t fit in anywhere, and trying to fit into the world at large is awkward. I’ve only met one other asexual in the wild, outside of ace-specific gatherings. And I’ve never met someone else with ARFID. I’m constantly on the lookout for others like me in the world, to know I’m not alone. I cling tightly to stories like Tim Gunn’s three decades of celibacy or Anderson Cooper’s encounters with pretty much any kind of food, desperately hoping that they are like me, that they understand, that I’m not the only one.

Cultural Prevalence

Much has been written about pointless, gratuitous sex scenes appear in practically every movie or TV show. Well, food does the same thing sometimes. Don’t believe me? Watch pretty much any travel show. Do they focus on the beautiful scenery and quaint villages and all the landmarks and vista points that I should be sure to see? No. It’s smug assholes like Anthony Bourdain telling me that I’m practically inhuman if I don’t want to wander the planet eating Scorpion on a Stick or drinking Peruvian Spit Beer. (And you know what? There are places in the world that I would love to go see, but I’m afraid to go because there is a very real chance that I will actually starve to death if I try.)

And don’t get me started on “food porn”…

Greatly Grace!

Design is available for sale, benefitting the Seattle Aces.

Astoundingly Aro!

Design is available for sale, benefitting the Seattle Aces.

Delightfully Demi!

Design is available for sale, benefitting the Seattle Aces.

Totally Ace!

Design is available for sale, benefitting the Seattle Aces.

Missing a Permission Slip

[Content Warning: Discussion of masturbation and sex and stuff.]

Not too long ago, over on Asexual Activities, there was a discussion about aces having trouble masturbating in one way or another. So I started writing about the problems I encountered learning how to do it. Along the way, I realized that there was something else getting in the way that I’d never really thought about too much. It’s always been there and the strength of it comes and goes, but it touches pretty much every interaction I have with sexuality.

I don’t feel like I have permission to have sexuality. It doesn’t feel like it’s mine. It’s like I stole it from someone else and I’m going to get in trouble if someone finds out that I have it. And I’ve never read the instructions, so I have no idea how to use the thing anyway.

I know that sort of sounds like guilt or shame, but it doesn’t really feel like that’s what it is. Guilt or shame implies that I think I’m doing something shameful or that I’m guilty of doing something wrong. I know it’s not anything that’s wrong and I know it’s not anything that’s shameful. It’s like one day I discovered that there was a mysterious $1000 deposit in my bank account. It’s not mine, I don’t know where it came from. I should tell the bank that they made a mistake, but everyone else says that they got the same mysterious deposit, and they’re going around spending it, with the bank’s blessing. But I don’t know what to spend it on and it doesn’t really belong to me, so I keep it in the account. I check on it once in a while, and it’s always still there.

Let’s start by getting some terminology out of the way. I’m not using “sexuality” as a synonym for sexual orientation. I am asexual, and that’s not in doubt. It’s likely even a large contributor to why I feel this way. I’m using “sexuality” to refer to my feelings, thoughts, interactions, reactions related to sex and other stuff in that general neighborhood.

Now, some statements of fact which feel relevant to what I’m going to talk about: I own a penis. I experience physical arousal. There are external factors which sometimes cause physical arousal. I masturbate. I enjoy it. I have sex toys. I look at porn. I have had sex twice. Fifteen years ago. I live alone. I am asexual.

When I hit puberty and first learned how to masturbate, it was something beyond top secret and fraught with peril. Messages from all over were telling me how terrible it was. You’ll go blind! You’ll grow hair on your hands! You’ll go sterile! It’s a sin! It was something only losers did. My ultra-Christian neighbor from an American Taliban household even gave me a mixtape that had a Christian Punk song about how “Masturbation is artificial sex” that probably detailed the eternal fiery horrors that awaited those who went downtown. (Fun fact: The pervy neighbor kid mentioned in the other post? Same guy.) Of course, none of those messages were coming from my parents. They never talked to me about it, but I suspect their thoughts would have been “Lock the door and clean up after”. But those messages were so pervasive from other places that they absolutely tainted how I felt, even though I didn’t believe most of them.

And it tainted what I did. No one could ever find out. I would take precautions worthy of an undercover agent. Only in the shower, where the evidence will be washed away and if someone walks in, I can say I’m just cleaning it, nothing else going on. Eventually, that expanded to being willing to do it while sitting on the toilet, but in that case, I had to use toilet paper to wrap myself and catch every drop. (Not sure how I was going to explain that if someone walked in…)

Either way, securely locked in the bathroom was the only place I was willing to do it for years. On extremely rare occasions, I would grab a bit of hand lotion from the front room, but that felt like a mission behind enemy lines. The house had to be vacant and expected to remain that way for hours if not days, all the doors were locked and checked, all the rooms were cleared, and then I’d make my move, grabbing a bit of lotion and running to the safety of the locked bathroom. I was terrified that every milliliter of lotion was being tracked and that I’d be discovered, so I did not do this often.

Eventually, I worked up the courage to try it in my bedroom. I think my parents were going to be gone for the weekend, and I was home alone. I triple checked the house to make sure it was empty, closed all the curtains in the house, checked the garage to make sure their car was gone, locked all the doors, then went into my bedroom and locked that door, too. I didn’t strip naked and get comfortable on my bed in order to have the most relaxed and pleasant experience possible. Instead, I was kneeling in front of my bedroom window, watching the driveway through a crack in the blinds, just in case. I kept my clothes on and did the deed through my fly. Not only was it all wrapped up in toilet paper, I added a layer of paper towel, to be extra special sure that everything would be contained. That happened maybe twice, total. Too risky.

Masturbation was something I did, but not something I felt I was allowed to do. It felt good, but it really wasn’t something I was able to enjoy, because I constantly had to be on guard or taking steps to hide the evidence.

I mention all of this, not to tell funny/embarrassing stories of my youth, but to detail how secret and forbidden I felt the whole thing was, and the lengths I felt I had to go to to conceal it. And certainly, I’m sure that other teenagers went through the same sorts of cloak-and-dagger routine to hide what they were doing. But some of that never left me.

Fast forward, years later. I have my own place. I knew by then that masturbation was common and that it didn’t cause random hair growth, etc. It had, by then, largely turned into something I was able to enjoy. But there were still limits. It was still done in the shower most of the time. I was able to occasionally work up the nerve to do it naked and relaxed in bed, but that was rare. I lived alone. No one would catch me, no one would know, but still, it somehow felt like the locked bathroom was the only truly private, safe place I had.

I had moved beyond using toilet paper and had discovered that various lubricants worked much better. But those had to be purchased. At a store. Where I had to get them off a shelf. Where I had to walk around the store with the item in my cart. Where a checkout clerk had to scan them. They are going to know. They are going to know why I’m buying hand lotion. They are going to know and they are going to report me.

Buying sex toys was a multi-faceted operation. First, finding the toy involved a lot of false starts and cleared search history. When I finally found something, it was probably a couple of weeks before I actually made the purchase. I used a second browser and completely cleared out the history when I was done. No one else ever used my computer, but you could never be too careful. (Not to mention the fear that the computer would somehow glitch out and start forwarding the order receipt to everyone I knew, or that it would set a picture of the item as my wallpaper and not let me change it.) Then, when the item arrived, it was dropped off at the leasing office, so I had to go in to pick it up. They have x-ray eyes or the box broke open so they know somehow. They know. They’re all going to laugh at me and I’m going to get evicted now. I even remember thinking that my new job would find out about it somehow and fire me.

Who did I think was going to find out my dark secret? Why did I think it was a dark secret? I knew there was nothing wrong with it, but why did it feel wrong?

But no, not wrong. Not bad. Not in itself. It wasn’t about someone discovering that I masturbate, it was about someone discovering that I was in possession of something that didn’t belong to me. That act, those feelings, that glimmer of sexuality, I wasn’t supposed to have that. I could pretend that it was mine, I had learned how enough of it worked to get by, but in the end, it wasn’t mine. And any time I tried to embrace a part of it or expand on what I knew, that put me at risk of the whole thing falling apart. Changing routine is what gets you caught.

I’ve been talking about masturbation a lot, because that’s my primary interaction with the world of sexuality, it’s not just that I feel like this about. Anything remotely sexual seems to set off the same alert buzzers in my head. I remember agonizing for a month about whether or not I should stop by the Student Health Center at college to pick up a free condom, because it seemed like a good idea to know how they worked. Even when I went to the health center a couple of times for something unrelated, I couldn’t bring myself to grab a few, because someone might see me. For years, any sort of undressing had to be done within the protection of the locked bathroom. I couldn’t change at the closet where all the clothes were. If I didn’t have a towel after a shower, I would have to dart to the hall closet to get one, after carefully peeking my head out the door to make sure no one was around. Sleeping in the nude was right out. Hell, sleeping in anything less than full clothes on even the hottest nights wasn’t something I felt I could do. (And this is all when I lived alone in my own apartment and there was no reasonable expectation that anyone would be there.) Whenever coworkers or friends talk about sex, I tend to shut off and pull back into my shell. Certain types of sex scenes in movies make me uncomfortable to watch. Beaches in Hawaii were unpleasant because of the amount of skin present.

While things have changed and gotten better over the years, this still comes up even today. I rarely go downstairs in my house unless I’m fully dressed. I still think that the mail carrier and neighbors will know what’s in certain packages I get, or that some package thief will grab one and blackmail me over what’s inside. Any book that’s remotely sex related (Even a general anatomy reference guide) doesn’t get put on the bookshelf, it gets hidden. So does any movie with “too much sex” in it. I’ll clear my clipboard if I ever copy/paste something remotely sexual. I’ll hide the hand lotion whenever someone comes over. Sex toys are removed from the closed cabinet in the headboard (that no visitor would ever open) and hidden in the closet. I even feel weird about having a box of tissues near my bed, because of the potential association it might have, even though I really do only use them to blow my nose. And I’ll censor what I talk about or feel weird about posting on Asexual Activities, even though that was deliberately designed to be an uncensored place to talk about those sorts of things.

And it’s not a general “Sex is bad, run away” reaction, either. When I’m in a scenario where I have permission, where sexuality is expected, it’s fine. When I had a girlfriend, we did sexual things. I was awkward and I had no idea what I was doing really, but I didn’t feel like I shouldn’t be doing any of it. At work, I had to test the adult filter settings on a service we ran, which basically meant searching for porn all day and making sure that the nudie pics showed up in the results or were blocked, depending on the settings. That was just doing my job. And I can dive in and research all sorts of random things for people who have questions on Asexual Activities, without any issues at all. But if I want to know about those things personally, I get a bit nervous.

So, what’s going on? Why do I feel this way? Why do I have so many blocks and caution signs put up around so many expressions of sexuality, even when they’re completely private? Well, the two broad areas that I think are coming into play here are society’s views on masturbation (specifically male masturbation) and the fact that I’m asexual, and the way those two things interact.

Society basically requires men to masturbate. If you don’t, you’ll be a two pump chump, your balls will fill up and explode, you’ll become a slobbering ball of horniness, and you’ll get cancer. But masturbation is only permitted in very specific scenarios. It must only be done when there isn’t a suitable partner available, and when it is done, it must be done while fantasizing about an acceptable person. And regardless, you’ll be mocked and ridiculed for doing it. You’re a pervy loser who can’t get laid.

Masturbation is seen as a replacement for “real” sex. You’re not supposed to do it if real sex is available. If you are forced to do it, due to a lack of real sex, you must be imagining having real sex with someone while you do it. It is not to be done within the context of a relationship, unless it somehow involves your partner, because the involvement of your partner allows you to claim that you’re doing it for them. It’s never permitted to be pursued in its own right, it must always be a substitute, never the main event, and any pleasure you take from it must be surrogate pleasure that’s being provided on behalf of your fantasy.

You can use porn to help, but not too much of it or the wrong kind of it. Oh, and by the way, any amount is too much and any kind is the wrong kind. Possession of nudity in all forms makes you a pervy loser worthy of mocking and ridicule. (Unless it’s an oil painting, a sculpture, or soft-focus photograph, then that’s art and therefore perfectly acceptable. But you’re not permitted to be aroused by that in any way.)

Sex toys are an absolute no when you’re alone. If you’re a pervy loser for masturbating, you’re an especially pervy loser if you use a toy. If you’re using a toy, you’ve given up hope of ever getting “real sex”, so you’re trying to find a second-rate simulation with a sleazy blow up doll. You’re so perverted that you’d rather fuck a rubber pussy than use your hand. And if the toy gets you off, you must have the hots for an inanimate object. It doesn’t help that sex toys for men have a stigma of being creepy and weird (likely because so many of them actually are creepy and weird).